A famous prehistoric cave site in Belgium has yielded the oldest multifunctional tool of its kind. This Ice Age “Swiss Army knife” wasn’t crafted by early Homo sapiens, however. Instead, the handy accessory came from our evolutionary cousin, the Neanderthal. The findings are detailed in a study published in Scientific Reports.

Neanderthals often get a bad rap. Despite mounting evidence to the contrary, many present-day Homo sapiens still believe that the archaic lineage died out largely because they were essentially dumber than their Cro-Magnon competitors. But while their cognitive abilities may have played a part in the larger story, Neanderthals simply weren’t as less-evolved as they’re depicted. For example, in 2024 researchers discovered what appear to be tchotchkes collected by Neanderthals at the Prado Vargas Cave system in Burgos, Spain.

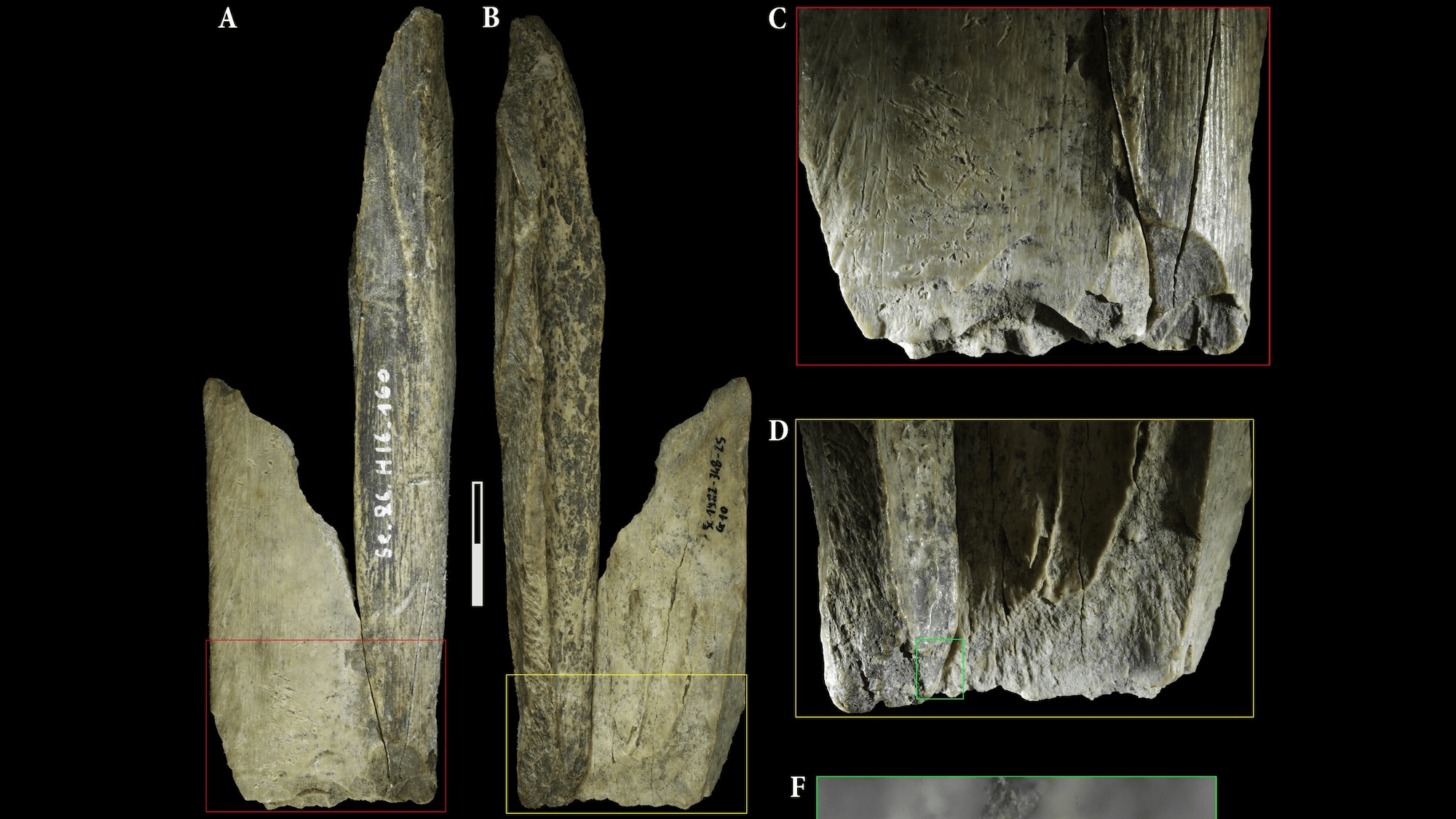

More recently,a team conducting ongoing excavations at Scaldina Cave archeological trove in central Belgium found an animal bone with clear indications of intentional shaping. Further analysis showed it to be a tibia bone from a cave lion (Panthera spelaea), a species of extinct panther that roamed present-day Europe until roughly 13,000 years ago. Additional tests also indicated the bone is around 130,000-years-old, dating back to the end of the Saalian glaciation period.

Archeologists at Belgium’s University of Ghent were particularly intrigued by multiple intentional markings carved into the bone. In all, the team determined that the tibia featured four separate tools, as well as signs of repurposing. The study’s authors theorize that some of the tools were initially utilized for jobs like chiseling. Later, Neanderthal artisans broke the bone and reused it for crafting flint tools—a process known as retouching. While the multitool’s additional uses remain unknown, the team argues it offers decisive evidence of Neanderthal ingenuity.

“The intentional transformation of lion bones into functional tools highlights Neanderthals’ cognitive skills, adaptability, and capacity for resource utilization beyond their immediate survival needs,” they explained in the study.

Beyond its direct usage, the bone tool also helps contextualize Neanderthal’s relationship to cave lions, which coexisted alongside them for hundreds of thousands of years. Other archeological sites have yielded evidence of lion skinning and butchering, but the Scaldina discovery is the first time experts have found a tool made from one of the animal’s bones.

Additionally, the methods Neanderthals used to make the lion multitool are identical to those found on other items in the cave, including some made from bear bones. Because of this, the study’s authors argue it’s possible Neanderthals didn’t attach much symbolic meaning to the animals—or, at least, no more than they did for the bears. Instead, they likely hunted these animals out of practicality.

The researchers hope to continue studying the latest find to potentially determine its additional uses. Meanwhile, the tool offers other archeologists an example to search for at other dig sites. In any case, one thing is clear: it’s time to give long-maligned Neanderthals the credit they deserve.

Source link