Scholars believe they have solved a medieval manuscript mystery that’s plagued scholars for nearly 130 years. Based on a handful of grammatical reevaluations, experts believe that they can reconcile a famously odd portion in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. In doing so, they also traced the text back to a priest from the Middle Ages who employed “memes” of the day as a way to relate to his parishioners. Their findings were published in The Review of English Studies on July 15.

Elves and adders–The ‘Song of Wade’

The Song of Wade was an extremely popular tale throughout the Middle Ages. At the height of its notoriety, the central character was as culturally recognizable as knights like Sir Gawain and Lancelot. Related folk-legends and epics tell the story of Wade’s courtship of a woman named Bell alongside a cast of characters including Wade’s supposed father, Hildebrand.

By the 1300s, the Song of Wade was ubiquitous enough for Geoffrey Chaucer to reference it in two separate works, including The Canterbury Tales. In “The Merchant’s Tale,” the 60-year-old knight January alludes to Wade’s boat while arguing in favor of marrying younger women.

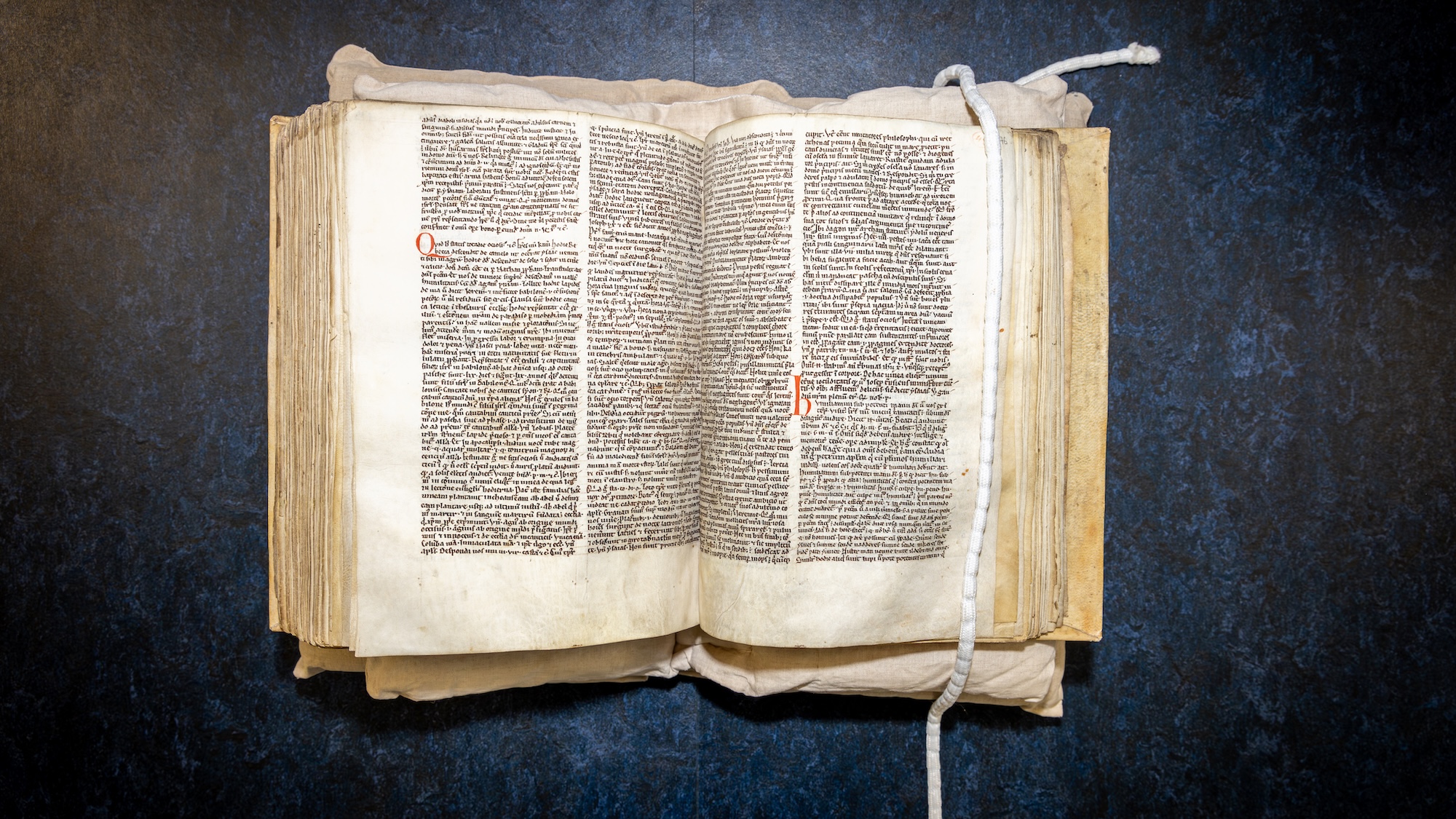

However, over the generations, primary sources for the Song of Wade were lost to time. The only major direct texts trace back to an accidental discovery by the renowned scholar M.R. James. While parsing through Latin sermons in the University of Cambridge archives in 1896, James unexpectedly found passages written in English, later known as the Humiliamini sermon. After consulting with fellow scholar Israel Gollancz, the pair eventually determined the Humilianmini section quoted a long-lost, 12th-century version of the Song of Wade. In it, the author curiously made it sound like the tale was far more fantastical than a grounded chivalric romance. For example, the sermon’s version describes Wade’s father as a giant, while another striking portion reads:

“Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters…”

Muddled letters

This translation simply didn’t make sense to several Chaucer scholars. They couldn’t figure out why the poet’s tale of courtly intrigue referenced a version of Song of Wade that includes mythical creatures.

“Lots of very smart people have torn their hair out over the spelling, punctuation, literal translation, meaning, and context of a few lines of text,” said James Wade, the study’s (aptly-named) co-author and an English literature scholar at the University of Cambridge.

After careful analysis of James’ finds, Wade and medieval history scholar Seb Falk concluded that it’s three specific spelling errors from the document’s scribe that have caused the decades’ worth of confusion. The biggest issues stem from muddled instances of the letters “y” and “w.” When corrected, the passage doesn’t mention elves—but wolves:

“Some are wolves and some are adders; some are sea-snakes that dwell by the water. There is no man at all but Hildebrand.”

Medieval memes

With the erasure of otherworldly beings and reducing Hildebrand down to a normal size, the Song of Wade becomes much more in keeping with a standard chivalric romance of the era.

“Changing elves to wolves makes a massive difference,” Falk said. “It shifts this legend away from monsters and giants into the human battles of chivalric rivals.”

But while this might solve the Chaucer confusion, it highlights an interesting decision made by the sermon’s author. Wade and Falk argue the author is the famous medieval writer, Alexander Neckam (1157-1217 CE).

“Many church leaders worried about the themes of chivalric romances–adultery, bloodshed, and other scandalous topics–so it’s surprising to see a preacher dropping such ‘adult content’ into a sermon,” said Wade.

Falk even goes so far as to describe the homily references as medieval “memes.”

“Here we have a late-12th-century sermon deploying a meme from the hit romantic story of the day,” said Falk. “This is very early evidence of a preacher weaving pop culture into a sermon to keep his audience hooked.”

In their translation of Neckam’s sermon, the speech intended as a lesson in humility, albeit imparted in odd ways. It largely focuses on Adam’s fall from grace, and compares humans to animals. Powerful men are likened to wolves when they take what doesn’t belong to them, while deceitful individuals are described as adders or water-snakes.

“This sermon still resonates today,” said Wade. “It warns that it’s us, humans, who pose the biggest threat, not monsters.”

Source link